When Form Betrays Function.

Why Robot Size is Foundational

By Michael McDaniel

Size matters.

Make a robot the size of a toaster and humans ignore it. Make it the size of a building and they run away screaming like Skynet just launched its first wave. Make it human-scale and suddenly they’re awkwardly trying to decide whether it’s a friend, a competitor, or a rogue killing machine here to purge the galaxy of meatbags.

Physical scale is such a powerful, subconscious signal that it’s long been used in storytelling to communicate intent before a character ever speaks. Villains are often oversized — superhuman in scale to intimidate or overwhelm. Heroes are typically human-scale (relatable) or sub-human, like WALL-E, to trigger empathy. From David vs. Goliath to modern sci-fi, scale is narrative shorthand.

After 25 years designing everything from brand systems and UIs to robotic construction platforms the size of small houses, I’ve landed on a simple but overlooked truth: humans treat machines based on size before they ever assess function.

We make assumptions about a robot’s intent and intelligence within seconds, based purely on its silhouette. The pattern is so deeply ingrained, we don’t question it:

Big = Threat.

Human or sub-human scale = Safe.

But it’s not just size. It’s also form. Build something the size and form of a small dog — four legs, central body, and any kind of expressive front end (eyes, head, ears, eyebrows, or just two LEDs) — and suddenly it’s a sidekick. A therapist. An emotional support unit. Swap the form to two arms and two legs, make it smaller than a person, and now it feels like a mischievous monkey. A clever trickster. A helper with opinions.

This is where interaction begins — not with AI, not with features — but with shape and scale. It’s the first moment in human-robot UX no one’s talking about… and it’s time we did.

Physical size sounds basic, but it’s often ignored in robotics. We’re biologically wired to judge intent through scale — a survival instinct shaped by thousands of years of fight-or-flight conditioning.

Is this large, fast-moving thing here to help me… or eat me?

As a rapid decision-making framework, scale works. If something is much larger than you, it’s probably more powerful. Add even the implication of intelligence and suddenly… you get a monster. Giants, dragons, ogres, yetis — they’re all larger than humans and all considered dangerous. These myths track with nature: bears, lions, crocodiles — all big enough to put a human in their belly. That makes us food. And food runs.

Now reverse the formula. Want something to feel safe? Make it smaller. Easy to dominate. Easy to control. You get R2-D2 — loyal, helpful, vulnerable. Not just unthreatening… endearing. Size triggers our protective instincts instead of our defenses.

This subconscious wiring isn’t lost on storytellers — they use scale as shorthand to convey emotion and power dynamics in seconds. C-3PO is human-scale. Want a scary version? Scale it up, broaden the shoulders, paint it black — and now you’ve got K-2SO, who looks like he could punch through a wall and quote protocol law while doing it.

Scale and shape aren’t decorative. They’re declarative.

If we want robots to feel useful, safe, or even lovable — we have to stop designing for function and start designing for presence. That starts with scale and form.

Most modern robots are built like tools — not characters.

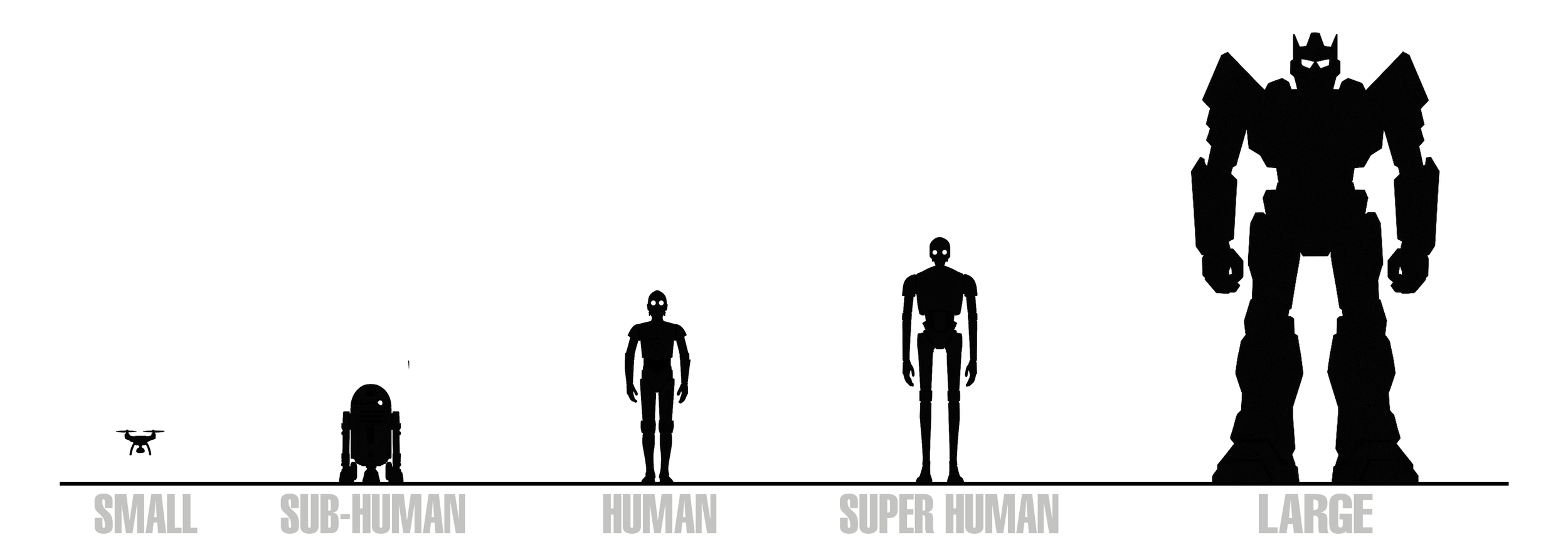

Its degrees of freedom on every joint rather than degrees of expression, let alone which forms of expression are appropriate at which scale for the desired output. Scale and form not only dictate behavior, they set the stage for which interactions are appropriate when. So here’s the framework I’ve used over the past few years to design robots and human-robot interactions. It isn’t based on function. It’s based on how humans behave and interact around machines at different sizes. It helps avoid uncanny valley moments, emotional friction, and outright primal fear.

Let’s start on one end of the framework and work our way up.

Small scale

Drone-size, handheld, insect-like.

These are the bots you can hold in your hand — or lose under your couch. They don’t trigger rich emotional engagement. They’re too small, too simple. Communication tends to be visual, functional, or entirely one-directional. When was the last time you had a meaningful exchange with a bug?

They’re useful, not emotional. Too small to connect, too simple to care. Their small scale defines their applications – documentation, data gathering and surveillance – all passive more one way interactions with rather than deep emotive connections.

Sub-human scale

Under 4 feet. Pet-scale.

This is the scale of empathy. Of naming. Of sidekicks. Of domestication. A robot the size of a small dog with just a touch of expressive motion and you have a companion, a friend – not an ‘it’. These robots invite projection. We name them. Protect them. Assign them emotional roles — just like we’ve done with animals for thousands of years.

Human scale

Roughly human-sized. 4–6 feet tall. Approachable, relatable… and uncanny.

This is the Goldilocks zone for meaningful interaction — but also the danger zone for discomfort. At human scale, a robot can make eye contact. Stand shoulder to shoulder. Sit at your dinner table, desk, or walk beside you down the street. That gives it just enough presence to feel like a peer — or a threat.

Everything about form and behavior becomes amplified at this scale. A subtle movement becomes a gesture. A long stare becomes creepy. Poor posture becomes menacing. Lack of emotional feedback becomes deeply unnerving. Because of their similar size, humans are constantly comparing themselves to them subconsciously looking for deltas - warning signs.

Human-scale bots can become teammates or tools, depending on how they’re designed — but screw up the silhouette, and you’re deep in uncanny valley territory. Make them on the larger side of the human spectrum (over 6’ tall) and they become menacing.

This is the scale where humans expect personality, because of the constant comparisons. We expect them to behave like us with any deviation from human norms flagged as abnormal. Murderbot is socially awkward because it doesn’t like eye contact and has no idea what to do with his arms standing near people. So every micro interaction whether intended or not is being judged at this scale. This is why this scale of robotics can so quickly fall into the uncanny valley – unless you’re actively running your “act like a human” subroutine.

Human-scale is where social UX begins to matter most. This is the scale where presence, posture, and emotional response aren’t optional—they’re mandatory.

Super Human scale

Taller than 7 feet. Broad. Heavy. Powerful.

This is where machines start to outsize us – to physically look down on humans. At this scale, their presence triggers awe or fear. Often both. AT-ATs walkers towering above the snow on Hoth were designed to incite fear with scale alone.

At this scale a robot’s job is to protect people, move heavy loads, or serve as a physical boundary. But lean too hard into anthropomorphism here, and things get weird. A 9-foot-tall Roomba with eyes darting around a room is not endearing. It’s nightmare fuel.

At Superhuman scale or larger, robots are rarely expected to converse with deep dialogue. They are sentinels. Load-bearers. Defenders at best or a powerful Enemy at worst. In fact, at this scale one way to make a super human scale robot feel friendly, is to handicap it. The Iron Giant invoked fear at first sight, but with its lack of verbal speech – it became an oversized companion and protector.

To succeed at this scale, robots must pair back the number interactions to still be rapidly assessed as a friend rather than a threat. This is not the realm of cuteness or cleverness. It’s the realm of deliberate motion and considered types of interactions. The moment a robot at this scale acts erratic or displays human level intelligence is the moment people run.

Large scale

Construction-scale. Bus-sized and larger. You don’t walk next to these machines — you walk around them.

At this size, robots stop being characters. They become creatures. We no longer expect them to talk. We expect them to roar, rumble, or breathe through hydraulics. They communicate like animals do — through motion, sound, posture, and rhythm because if you start applying human-like behaviors to them then people start looking for weapons to defend themselves.

This is the scale I know best. I’ve spent years designing and refining robotic construction platforms the size of large vehicles — systems capable of printing entire homes. At this scale, humans don’t project emotion onto machines. The sheer size and unfamiliar silhouettes break our mental models. There are no real-world Jaegers or upright mechs to anchor against. These machines don’t resemble animals or humans, which means motion must be intentional and expressive in new ways. What’s its “face”? Is that an arm or a tail? Does it jitter and lurch, or does it move with the grace of something aware of the fragile humans around it? These details matter. Scale demands a different kind of choreography — one that communicates power, purpose, and restraint.

Robots on this scale need posture. Predictability. Rhythm. This allows them to be more than a machine without invoking fears of AT-AT stomping you flat.

Big robots operate in our world, but not with us. They aren’t sidekicks or assistants. They’re apex collaborators — and their UX lives in how they telegraph force, focus, and constraint.

Robot scale framework

We’ve spent years trying to teach robots to speak human — through natural language, facial expressions, even emotional reasoning. But the truth is, by the time a robot opens its mouth (if it even has one), we’ve already made up our minds.

Human-robot interaction doesn’t begin with conversation. It begins with presence. With scale. With silhouette.

These are the first signals we process. Before the robot moves. Before it speaks. Before it runs its first line of code.

As designers, engineers, and builders of machines that will live among us, we need to stop starting with features — and start with feeling. Start with the gut. The glance. The threat assessment. Because if your robot fails the first five seconds, it doesn’t matter how smart it is. It won’t be trusted. It won’t be used. It won’t be welcomed.

That’s why I built this scale framework. Not as a taxonomy of form factors, but as a lens to understand what kind of relationship each scale enables. From tiny tools to expressive sidekicks to apex collaborators, robot UX is defined by scale before it’s defined by function.

So the next time you’re designing a robot — whether it’s a printer the size of a elephant or a rover that follows you around like a caffeinated squirrel — ask yourself the first and most important question:

“What should this feel like in the room with me? ”

That’s where the real design work begins.